Ecommerce is not as big a deal as you think – it’s in fact much bigger a deal than you think. Flummoxed?

Mind this! In this fast, fast world of vanishing moments of patience, ecommerce has come up as the best fix with convenience, comfort, and choice – all bundled into one – delivered at your doorstep. Little wonder, India’s $103 Bn ecommerce market is on course to create a by 2030.

But the deal doesn’t end there. The ease of distribution on ecommerce made it easy for emerging segments like direct-to-customer (D2C) to grow into a and quick commerce to zoom into a segment.

With a manpower resource running into millions, an industry-wide , and potential to of an estimated $7 Bn Indian economy by 2030, ecommerce is indeed far bigger a deal than ever imagined.

Mind this, too! While the role of ecommerce behind the making of some of the most significant D2C brands remains indisputable, the hefty cost of building a brand on these platforms remains overlooked in most cases.

Ecommerce has removed the presence of intermediaries in the distribution network, but it has slapped commissions on small entrepreneurs. The online marketplaces helped them reach a wider section of consumers, but also asked them to cough up the cost of advertising. If ecommerce helped brands with logistics, then it charged for storage and returns as well.

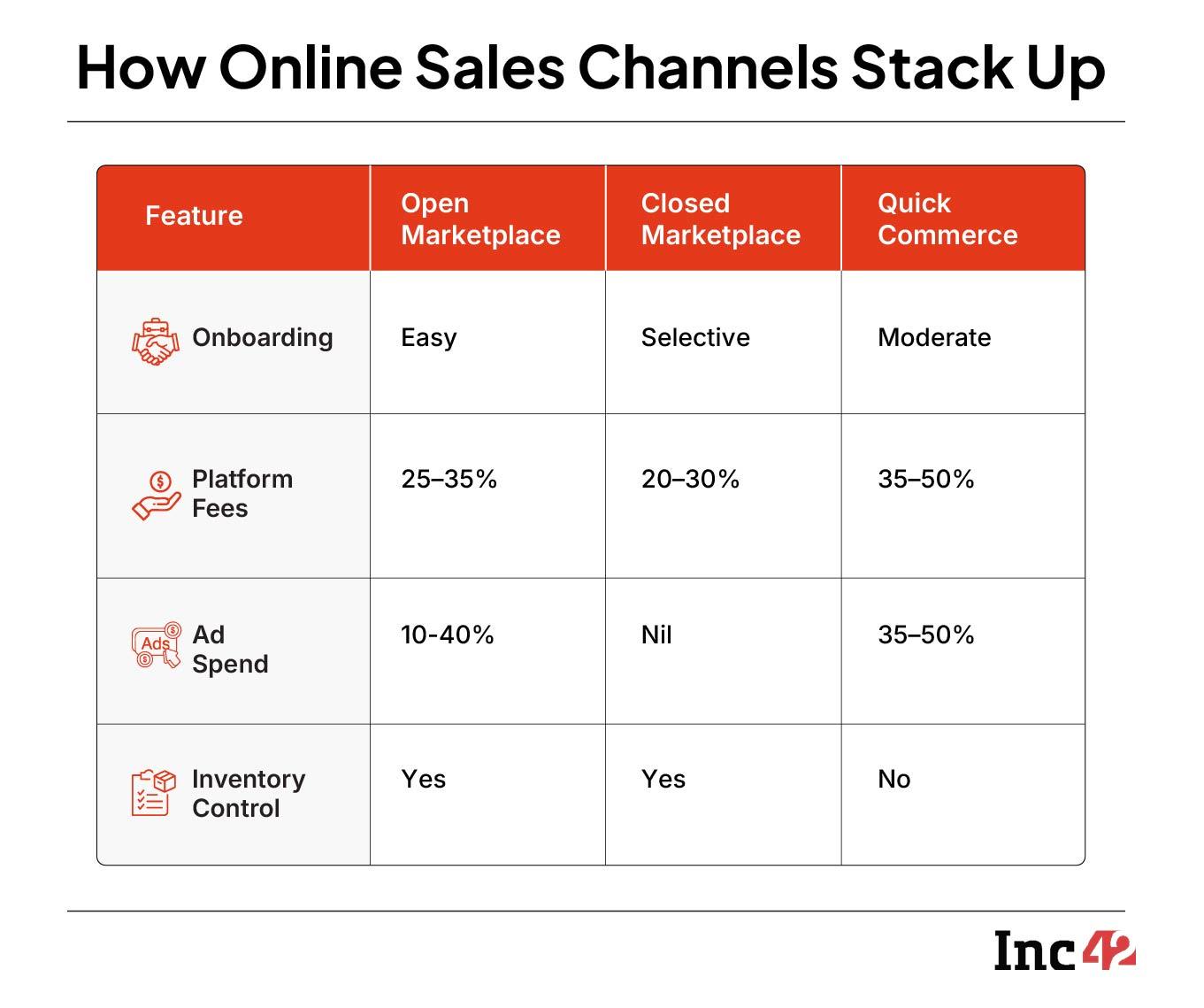

The multilayered levies in the form of platform fees, commissions, storage charges, delivery costs and advertising expenses have grown as a major cause for concern for D2C brands building on the ecommerce ecosystem. For open marketplaces like Amazon and Flipkart, the platform fees alone can range from 30% to 40% of the selling price, depending on the product category and the scale of the brand, an Inc42 probe has revealed.

That’s not all. The brands also need to pay the GST on the sales done on online marketplaces. They have little choice but to bear the payment load while also investing heavily only to remain visible to consumers.

“As a new brand in a highly competitive category like home décor, after spending on ads and platform fees, we’re left with almost nothing at the end of the day once the sale is closed,” rued the founder of a fledgling brand with an annual revenue of INR 50 Lakh and multichannel presence. Most of the founders Inc42 spoke to chose to be anonymous because they rely entirely on ecommerce and quick commerce for their survival.

In fact, several founders of D2C brands pointed out that by the time a product is sold, often very little is left in hand. The noose around the neck has tightened with the rise of quick commerce platforms, where visibility is essential, but it comes at a steeper cost with platform fees shooting off to 50%.

A look into the fee economics of ecommerce and quick commerce will help better understand the maladies of platform fees.

Level Playing Field Or Profit Sinkhole?The rise of ecommerce giants like Amazon, Flipkart and Meesho have levelled the playing field for millions of small and medium enterprises (SMEs) and startups, throwing open to them a market run by the world’s with disposable incomes set to exceed by the time India turns 100, aided by a burgeoning hovering on 1 Bn+ in strength.

Amazon and Flipkart dominate India’s open marketplaces, allowing any approved seller to list and sell products. But behind this simplicity lies a complex cost structure that varies by fulfilment model, category, and ad spending.

Amazon offers sellers three primary models for fulfilling orders – all based on how the product is shipped and who handles the storage and logistics. Under Amazon Easy Ship, the seller manages their stocks, packs the products on getting an order, and then hands it over to Amazon’s pickup executive for delivery. This model does not involve storage charges but costs a logistics fee for Amazon’s shipping services.

The Self Ship model is based on the seller managing the entire fulfilment process independently. The seller handles packing, shipping, and delivery either through a third-party courier service or through its own network. Amazon charges only the listing fee and the closing fee.

In the “Fulfillment by Amazon” (FBA) model, Amazon manages everything from storage to delivery. The seller pays multiple fees for storage, pick-and-pack, and shipping. This is the costliest option for the sellers. “Yet, it gives more control and better exposure with priority listings,” said the founder of a D2C beverage startup. “Most D2C founders choose FBA because it has more visibility and higher conversion.”

Flipkart runs a broadly similar structure, though several founders noted that logistics and warehousing costs tend to be lower, especially for bulk shipments. “But Flipkart does not offer as much seller support or dashboard sophistication as Amazon, making it harder for early stage founders to optimise performance,” the beverage brand founder said.

Platform fee generally eats up 25–30% of the selling price, but it can go up to 30–35% when routed through third-party service providers. These agencies often help manage warehousing, account handling, or performance marketing, but charge a premium.

“For most merchants, this is significantly lower than the established channels of distribution where 40–45% of the manufacturer’s recommended retail price (MRP) ends up going to intermediaries and retailers,” said Vinod Kumar, president of the Indian SME Forum. “These platforms provide a simple point of entry, removing the need for initial expenses such as shelf rentals or distribution charges, while giving access to existing logistics and payment systems.”

Burden Of Ecommerce Platform FeesAdvertising fee has turned out to be a major factor, according to the founders. Digital ad spends on Amazon and Flipkart can range from 10% to 40% of the selling price, sometimes even 50–60% for new or lesser-known brands. “It’s hard to rank without ads, especially in categories like beauty and fashion,” said the founder of a beauty products brand. “You have to treat it like a paid shelf.”

A D2C startup with a yearly turnover of INR 10 Cr spends INR 7-8 Cr on advertising itself as it is in a very competitive category. “But the return on investment (ROI) from these ads is never much higher,” the founder claimed.

A typical consumer brand making INR 100 Cr annually ends up spending heavily – going up to INR 40 Cr at times – on ads if it’s purely D2C with no offline brand recall. A brand with INR 10 Cr in revenue shells out INR 6–8 Cr just on advertising, said Mayank Prasoon, founder of Datavio, which works with CPG (consumer packaged goods) brands, provides sellers with clean, actionable data insights that they can’t easily obtain or use from standard ecommerce seller panels and other sales channels.

According to Prasoon, ROAS (Return on Ad Spend) is critical, and it is heavily dependent on the category. For instance, a highly competitive category like protein bars might see an ROAS of around 1.5 to 3, while a less competitive or more established category like dairy or fresh foods can achieve much higher ROAS.

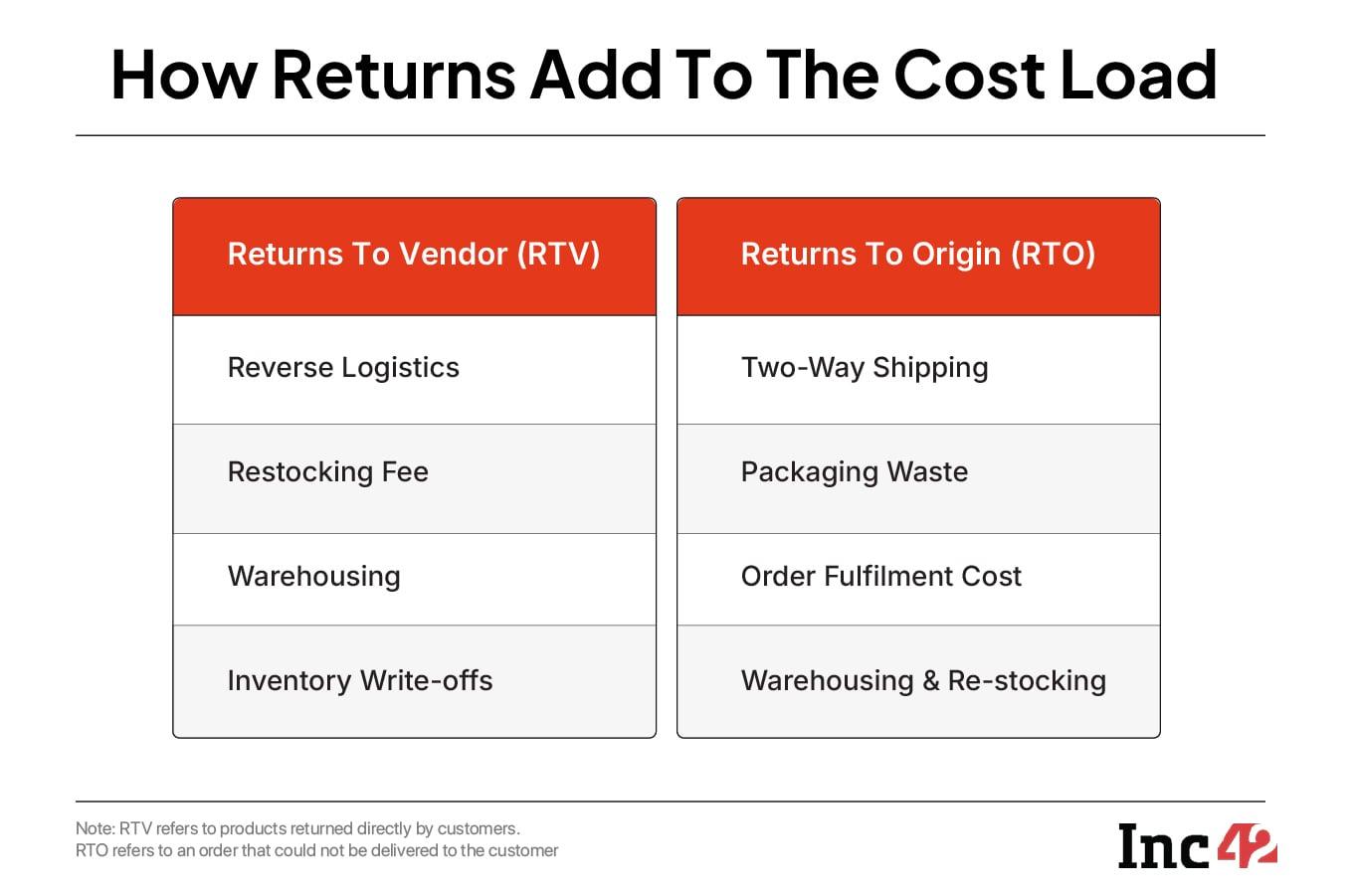

If the levies weigh too heavily on the sellers, then returns are additional loads they need to bear. Every returned product requires a separate quality check, adding significant costs. Imagine spending INR 100 per SKU, including delivery, advertisement, procurement, and manufacturing, and then another INR 50–60 just to process the return.

On top of this, sellers need a dedicated warehouse team to determine whether a returned product could be resold after quality control. Smaller sellers, particularly those with monthly revenues of INR 10–25 Lakh, often lack standardised QC processes for returned items. Many simply recycle returned products by sending them to other customers ordering the same item, but this practice can harm brand perception.

Unlike open platforms like Amazon and Flipkart, closed marketplaces such as Tata CLiQ Luxury, Tata CLiQ Fashion, and Ajio follow a curated approach. Here, brands can’t simply register and list their products. The onboarding is selective, often by invitation or only after a vetting process.

Once onboarded, fee structures are standardised and negotiated, usually involving a flat commission with logistics included. Founders say this model offers more consistency and stability. “There’s no bidding war for visibility. Once you’re in, your exposure depends more on your product and content quality,” said the beauty and personal care brand founder.

Ad spends here are minimal, if any at all. These platforms rely heavily on editorial curation, emailers, influencer tie-ups, and their own content and merchandising teams to promote the products. That brings down the effective customer acquisition cost, making them attractive for early stage brands focussed on storytelling and positioning.

Myntra, though technically an open marketplace, stands somewhere in between. It maintains selective onboarding and limits sellers by category. Commission rates are higher than Amazon or Flipkart, but many founders said ad spends are lower due to less-effective internal ads and a curated experience.

Then where is the problem? These platforms offer very limited market opportunities, a founder of a D2C home segment brand pointed out. “Hence, it is never possible to replace Amazon with these closed marketplaces and cannot compare directly as well.”

The surge of has set the online shopping turf ablaze. A raging duel between quick commerce and its gigantic predecessor, ecommerce, has left the D2C brands charred by multiple fees with churned margins. “Yet, staying on these platforms is non-negotiable. Simply because these platforms have taken over the modern distribution game,” said the founder of a D2C home décor brand.

Blinkit, Zepto, and Swiggy Instamart have emerged as undeniable channels for the distribution of products. With hyper-local, super-fast delivery, these platforms are fulfilling consumers’ growing need for convenience, delivering consumer products and groceries in minutes.

While these platforms offer tremendous reach and visibility, they command a premium for listing. The commission and fees on quick commerce platforms can range from 35% to 45% of the MRP. This is significantly higher than traditional ecommerce platforms like Amazon or Flipkart, where commissions typically hover around 20-25%. For newer D2C brands, this cost structure can be particularly challenging.

“If you take the route through a third party for Amazon, you essentially give 30% of your MRP. For quick commerce, the fee is between 35% and 45%, depending on the platform,” said the chief executive of a Mumbai-based skincare D2C brand.

These fees cover logistics, warehousing, and commissions, but for small brands attempting to build their reputation or customer base, the expenditure hardly ever pays them back through brand visibility or interaction.

Quick commerce platforms like Blinkit and Zepto tend to use the dark-store model, which again is a pain point for small sellers. Startups remain in the dark about how their inventory is handled or why certain products are given preference over others. For brands such as ClayCo, a skincare D2C brand, such platforms are more like distribution channels than brand-building opportunities. “You are there so customers can find you when they want you, it’s like a new-age version of general trade,” she said.

Kumar, the SME Forum chief, too described the commission and fee structures on quick commerce platforms as opaque. Sellers often fail to comprehend the break-up of the fees and commissions they pay. There’s also concern around margins, return policies, and a lack of clarity in how their products are marketed or prioritised.

These are the factors why sellers feel more comfortable with traditional ecommerce than with quick commerce. “In fact, quick commerce employs the worst of two worlds – the open and closed marketplaces. It requires high ad spends, but there is no transparent platform fee structure,” the founder of a D2C startup said. He listed his company on Zepto six months ago.

“Orders are still coming in, but the profits? Negative,” Arjun Vaidya, who introduces himself as a D2C founder and an early stage investor, . “Founders tell me: ‘I sold INR 2.1 Cr on quick commerce last quarter… And ended the month with INR 30 Lakh in losses. The platform takes 35%. The customer takes the discount and I don’t even get a phone number’,” he wrote.

Omnichannel Or D2C Pivot Offers A BreatherMost brands kick off their journey riding on the ecommerce or quick commerce boom. While they use Amazon or Flipkart or Blinkit or Zepto as launchpads, many of them move to the direct-to-consumer (D2C) route after they reach a certain scale. “Having a D2C channel offers multiple advantages – better access to customer data, a more personalised brand experience, and, most importantly, improved margins by avoiding a high platform fee,” said the founder of a D2C apparel startup.

But the D2C way is not free of challenges. “Running your own D2C website comes with its own set of expenses – ad spends on Google, Facebook, Instagram, plus the cost of setting up logistics and managing returns. Marketplaces take care of much of that,” Kumar argued.

In the absence of built-in traffic and a ready-made customer base of Amazon or Flipkart, D2C brands need to rely heavily on digital advertising to drive traffic to their websites. But with growing competition, the cost of advertising on Google, Meta, and Instagram continues to rise, pushing up the customer acquisition cost (CAC) further.

The D2C brands also face the burden of handling logistics, returns, and fulfilment on their own. While Amazon’s FBA model takes care of all of that, D2C brands must invest in warehousing, shipping infrastructure, and customer support. “Unless you’re ready to burn a lot of cash upfront, it’s hard to scale D2C to a level where you gain leverage,” said the skincare brand CEO.

For most founders, the decision of investing in a D2C platform vis-à-vis spending on online marketplaces ultimately boils down to their ability to absorb the costs of advertising, logistics, platform fees and transaction fees.

Marketplaces like Amazon and Flipkart offer low entry barriers and instant access to a vast audience. Quick commerce platforms like Blinkit or Zepto offer speed and convenience at a higher cost. D2C channels, on the other hand, offer higher margins and greater control but require heavy upfront investment in customer acquisition and operational infrastructure.

For most brands, the shift to D2C isn’t about replacing marketplaces altogether but finding the right balance as they grow. As India marches towards by 2030, the need for greater transparency, fairer fee structures, and seller-friendly policies is more urgent than ever.

[Edited by Kumar Chatterjee]

The post appeared first on .

You may also like

"World will be against Pakistan": Nishikant Dubey on all-party delegation to Saudi Arabia

Arsenal's electric starting XI next season if Mikel Arteta lands £176m trio

Summer Vacation 2025: School reopening dates for Delhi, UP, Bihar, MP, Rajasthan and other sates

Britney Spears warned for lighting cigarette amid flight

Lab Assistant: Recruitment is going on for the vacant posts of Laboratory Assistant in Bihar, candidates who have passed 12th class can apply..